How women was perceived in the Yazidi society of the 19th century

Murat Gokhan Dalyan

Cabir Dogan

Part 1

Introduction

This article examines the social status of Yazidi women and their place in the family hierarchy in order to find answers to the following questions : How were women perceived in Yazidi society? What was the role of women in public life?

"Because the Yazidi culture of the 19th century was not recorded by the Yazidis themselves, and because they were a rather small and secretive society, our knowledge of the Yazidis is very limited. Much of what we know about the Yazidis is based on the accounts of Western travelers and missionaries, who are also among the main sources of this article. Although several references have been made to the 20th century, the scope of the article is largely limited to the 19th century.

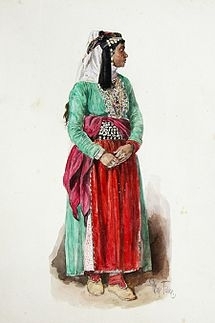

In 19th-century Yazidi society, women were second in the family due to Patriarchal family structures. Girls were often married off by their fathers in exchange for a bride price, often against their will. The most important status a woman could achieve in Yazidi society was loyalty to her family and housekeeping. Women usually had long hair, covered their heads, and wore long dresses. Yazidis were very fond of the color red in their dresses and avoided the color blue. Literacy was banned for both men and women. The social status of women remained unchanged even in the nineteenth century, as Yazidi society adhered to its traditions. Since the Yazidi faith regarded literacy as a taboo and banned it in the same century, all women remained illiterate.

Who Are the Yezidis? There is a plurality of views on the origins of the Yezidis, who are part of the great mosaic of the Middle East, but no consensus. Studies on the Yezidis generally accept that they are Near Eastern in terms of language and ethnicity, but that their religion is mixed throughout history with, Zoroastrianism, Christianity Although their faith contains elements of many different religions, the Yezidis jealously guarded the specifics of their principles of faith, which was noted by many as a curious phenomenon. W.B. Heard observes that from the late 19th century onwards, the Yezidis were subjected to propaganda by Christian missionaries, and began converting to Christianity (Heard, 1911). Because the Yezidi faith contained elements of Christianity, they were an attractive target for the missionaries (Jackson, 1904) . In 1911, regions where the Yezidis were settled in large numbers, called Sanjak by the Yezidis themselves, were as follows: 1-Sheikhan (Mosul and its vicinity), 2-Sinjar (Mountain Sinjar), 3- Aleppo, 4- Khatta (Mardin and Diyarbakır and their vicinities), 5-Zozan (Tigris and Batmansu regions, and Şırnak’s vicinity) 6- Haweri (Jezireh-ibn-Omar, on the two sides of Tigris), 7-Moscow (Trans – Caucasia) (Joseph, 1909; Heard, 1911; Millingen, 1998) . According to researcher Isya, the Yezidi population in the 1900s was around 200,000 (Joseph, 1909) and they usually lived in tents (Joseph, 1909) (Note 4). Although they originally earned their livelihood through animal husbandry, they also used to exact tribute from caravans that passed their way, and from foreigners (Shiel, 1838; Pollington, 1840; Ainsworth, 1842). Towards the end of the 20th century, most of the Yezidis, especially those in Anatolia, migrated to European cities (Bruinessen, 2005; Bruinessen, 2006.

As in all other middle Eastern societies, fathers marry off their daughters to the groom of their caste in exchange for a bride price, regardless of their own choice. The most important factors determining the price of a bride were the girl's beauty, the economic status of her family, and her status in the tribal hierarchy . Thus, the" price " of the bride can be higher or lower depending on the social status of the family. "Prices" (kalym) for the bride were higher among the higher strata and lower among the lower strata. However, the bride and groom had to belong to the same caste, regardless of the amount of the bride price.

In the early 19th century, Sinjar sheh Hamo shero set the bride price of a girl from the Sheikh layer at 1500 rupees/cents. In the same period, the bride price of a wealthy upper-class girl was 30 sheep or goats. The bride price also varied depending on whether the bride was a virgin or a widow. As a rule, the price of a widow's bride was half that of an unmarried girl. When a woman's husband died, her family could remarry her to someone else in exchange for another bride price. However, in the following years, the Qawwals, one of the religious castes-an itinerant group that sang hymns-were unable to find girls to marry from their own caste, and their population dwindled; they were then allowed to marry girls from one caste below. Ransom (kalym) for the bride can be in money, property or animals. However, since bride prices were often too heavy a burden for many, families also engaged in "berdel", also known as sister swapping, parallel weddings. Thus, both parties could enter into marriage without paying a ransom for the bride, making marriage more affordable. In cases where the berdel was not applicable and the parties could not agree on the terms of the bride price, the young men could also escape. However, this was considered a disgrace to the girl's family and tribe, and the girl's side took various measures to make the other side pay. Because escape was so strictly sanctioned by society, the young men who escaped often sought protection from the Emir or Sheh, who then acted as a mediator to reach an agreement between the families. If the mediation is successful, the parties will make peace in exchange for a certain amount of money to be paid to the girl's family, and the wedding ceremony will take place. However, this price will almost always be higher than the usual bride price of a girl, because the honor of the tribe will be at stake. Otherwise, blood will be shed between the tribes, and long-term blood feuds will begin. However, there were also cases where the fugitives were not caught, everything cooled down, and everything was simply settled. If girls do not wish to marry, it is considered that they must serve their fathers to compensate for the amount they would otherwise receive from future suitors. In 1909, Yazid Mir Ismail Bey set a price cap to regulate the price of a bride, which caused various problems in society. Escape as a result of high bride prices continued into the 20th century.

Tags: #yazidisinfo #езиды #историяезиды #езиды19век

How women was perceived in the Yazidi society of the 19th century

Murat Gokhan Dalyan

Cabir Dogan

Part 1

Introduction

This article examines the social status of Yazidi women and their place in the family hierarchy in order to find answers to the following questions : How were women perceived in Yazidi society? What was the role of women in public life?

"Because the Yazidi culture of the 19th century was not recorded by the Yazidis themselves, and because they were a rather small and secretive society, our knowledge of the Yazidis is very limited. Much of what we know about the Yazidis is based on the accounts of Western travelers and missionaries, who are also among the main sources of this article. Although several references have been made to the 20th century, the scope of the article is largely limited to the 19th century.

In 19th-century Yazidi society, women were second in the family due to Patriarchal family structures. Girls were often married off by their fathers in exchange for a bride price, often against their will. The most important status a woman could achieve in Yazidi society was loyalty to her family and housekeeping. Women usually had long hair, covered their heads, and wore long dresses. Yazidis were very fond of the color red in their dresses and avoided the color blue. Literacy was banned for both men and women. The social status of women remained unchanged even in the nineteenth century, as Yazidi society adhered to its traditions. Since the Yazidi faith regarded literacy as a taboo and banned it in the same century, all women remained illiterate.

Who Are the Yezidis? There is a plurality of views on the origins of the Yezidis, who are part of the great mosaic of the Middle East, but no consensus. Studies on the Yezidis generally accept that they are Near Eastern in terms of language and ethnicity, but that their religion is mixed throughout history with, Zoroastrianism, Christianity Although their faith contains elements of many different religions, the Yezidis jealously guarded the specifics of their principles of faith, which was noted by many as a curious phenomenon. W.B. Heard observes that from the late 19th century onwards, the Yezidis were subjected to propaganda by Christian missionaries, and began converting to Christianity (Heard, 1911). Because the Yezidi faith contained elements of Christianity, they were an attractive target for the missionaries (Jackson, 1904) . In 1911, regions where the Yezidis were settled in large numbers, called Sanjak by the Yezidis themselves, were as follows: 1-Sheikhan (Mosul and its vicinity), 2-Sinjar (Mountain Sinjar), 3- Aleppo, 4- Khatta (Mardin and Diyarbakır and their vicinities), 5-Zozan (Tigris and Batmansu regions, and Şırnak’s vicinity) 6- Haweri (Jezireh-ibn-Omar, on the two sides of Tigris), 7-Moscow (Trans – Caucasia) (Joseph, 1909; Heard, 1911; Millingen, 1998) . According to researcher Isya, the Yezidi population in the 1900s was around 200,000 (Joseph, 1909) and they usually lived in tents (Joseph, 1909) (Note 4). Although they originally earned their livelihood through animal husbandry, they also used to exact tribute from caravans that passed their way, and from foreigners (Shiel, 1838; Pollington, 1840; Ainsworth, 1842). Towards the end of the 20th century, most of the Yezidis, especially those in Anatolia, migrated to European cities (Bruinessen, 2005; Bruinessen, 2006.

As in all other middle Eastern societies, fathers marry off their daughters to the groom of their caste in exchange for a bride price, regardless of their own choice. The most important factors determining the price of a bride were the girl's beauty, the economic status of her family, and her status in the tribal hierarchy . Thus, the" price " of the bride can be higher or lower depending on the social status of the family. "Prices" (kalym) for the bride were higher among the higher strata and lower among the lower strata. However, the bride and groom had to belong to the same caste, regardless of the amount of the bride price.

In the early 19th century, Sinjar sheh Hamo shero set the bride price of a girl from the Sheikh layer at 1500 rupees/cents. In the same period, the bride price of a wealthy upper-class girl was 30 sheep or goats. The bride price also varied depending on whether the bride was a virgin or a widow. As a rule, the price of a widow's bride was half that of an unmarried girl. When a woman's husband died, her family could remarry her to someone else in exchange for another bride price. However, in the following years, the Qawwals, one of the religious castes-an itinerant group that sang hymns-were unable to find girls to marry from their own caste, and their population dwindled; they were then allowed to marry girls from one caste below. Ransom (kalym) for the bride can be in money, property or animals. However, since bride prices were often too heavy a burden for many, families also engaged in "berdel", also known as sister swapping, parallel weddings. Thus, both parties could enter into marriage without paying a ransom for the bride, making marriage more affordable. In cases where the berdel was not applicable and the parties could not agree on the terms of the bride price, the young men could also escape. However, this was considered a disgrace to the girl's family and tribe, and the girl's side took various measures to make the other side pay. Because escape was so strictly sanctioned by society, the young men who escaped often sought protection from the Emir or Sheh, who then acted as a mediator to reach an agreement between the families. If the mediation is successful, the parties will make peace in exchange for a certain amount of money to be paid to the girl's family, and the wedding ceremony will take place. However, this price will almost always be higher than the usual bride price of a girl, because the honor of the tribe will be at stake. Otherwise, blood will be shed between the tribes, and long-term blood feuds will begin. However, there were also cases where the fugitives were not caught, everything cooled down, and everything was simply settled. If girls do not wish to marry, it is considered that they must serve their fathers to compensate for the amount they would otherwise receive from future suitors. In 1909, Yazid Mir Ismail Bey set a price cap to regulate the price of a bride, which caused various problems in society. Escape as a result of high bride prices continued into the 20th century.

Tags: #yazidisinfo #езиды #историяезиды #езиды19век